Dominic's Take

Dominic's Take: To Innovate, Put Our Strengths and Values First

By Dominic Ng

East West Bank Chairman and CEO says new legislation has to help—not harm—U.S. businesses.

In the coming weeks, Congress will debate two versions of legislation meant to reinvigorate American innovation and competitiveness: the Senate’s “Make it in America Act” and the House’s “America COMPETES Act.” There are important differences between them, but both frame the innovation challenge as a competition with China.

In geopolitics, as in business, competition is not necessarily a bad thing. But what is needed today are measures that promote smart competition by playing to our strengths and values. On this front, Congress has more work to do.

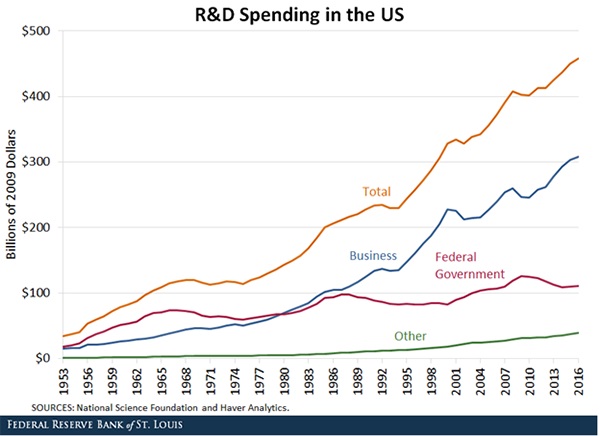

That work starts by recognizing where innovation comes from. In the past, two-thirds of American R&D came from government spending, with the rest coming from the private sector.

Today, that picture has flipped. With government spending mostly flat over the past four decades, businesses now far outspend government on R&D, and the contribution from government has fallen to just 24%. Thanks to private enterprise, the United States spends more on research and development than any other country and is the patent leader in high-tech sectors like information technology and biotech. Yet at the same time, flatlining government expenditure on R&D has made it harder to stay ahead.

It’s not just U.S. importers, but exporters too. In a recent study, 82% of surveyed U.S. companies doing business in China reported that trade tensions have impacted their business in China, and 22% reported losing sales in China due to retaliatory tariffs. Yet for most of these companies, China remains a crucial market—only 6% of surveyed companies plan to scale back their resource commitments to their China operations over the next year, while 43% plan to invest more.

It would be one thing if the costs borne by American businesses and consumers led to a better deal for the United States. But the gains from the trade war are murky at best. In the first instance, the trade war failed to deliver on one of Trump’s main goals—to lower the U.S. trade deficit, a goal that never really made sense to begin with. The U.S. trade deficit is now the largest it has ever been, but for reasons that have less to do with China and more to do with strong U.S. consumer demand as the economy emerges from the depths of COVID-19.

There are two powerful lessons to draw from this history. An innovation bill should reinvigorate federal spending, especially in ways that empower the private sector. And it should avoid including measures that could undermine the competitive strength of American businesses.

The phase one deal did secure commitments from China to address intellectual property and forced technology transfer issues, but it has not delivered the results many had hoped for. Only 7% of surveyed businesses said that the benefits of the phase one deal have clearly outweighed the costs of the tariffs. At the same time, the phase one deal included provisions calling on China to buy record amounts of U.S. goods by fiat—a demand that sidelined U.S. allies and undermined the market-based norms of international trade that the U.S. should champion.

With the trade war lingering on, the business community and some in Congress are asking the administration to find a solution. It is unlikely that the administration will fully roll back its tariffs on China—to do so would invite accusations of being “soft” on China ahead of the midterm elections and 2024 presidential race.

On that basis, the legislation now under debate earns a mixed review. On the one hand, though the House and Senate bills are not fully aligned, they both include much-needed funding for government scientific research. The Senate bill would authorize over $9 billion for a new directorate at the National Science Foundation focused on technology and innovation. Both bills include $52 billion in funding for semiconductor research and manufacturing in the United States.

The legislation also supports small business innovation by extending two important initiatives: the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs. These provide grants to small businesses working on innovative technologies that advance the American research agenda.

To the businesses awarded these grants, the results can be transformative. SOFIE Biosciences, a California-based company that develops compounds to identify and treat a wide range of diseases, won a $150,000 proof-of-concept grant for a new technology in 2011, which led to a $1 million prototype development grant one year later.

Not only did this funding allow them to take their research to the next level, but the review process involved with the award gave investors the confidence to support the company with their own capital—a perfect example of how smart government support can unleash private innovation.

While this is all to the good, the proposed legislation also has provisions that would inadvertently hurt, rather than help, U.S. innovation and competitiveness. The House bill, for instance, includes a provision that would require businesses to report any investment to China that touches on a broad range of sectors, including automotive, agriculture, and more. A committee tasked with reviewing these investments could forward a recommendation to the President to block these deals.

A measure like this poses many problems for businesses—and ultimately for U.S. competitiveness. A study by the Rhodium Group estimates that 43% of U.S. investment in China in the past two decades has been in sectors that could be covered under the bill. These are the makings of a bureaucratic nightmare, especially for small businesses without the resources or support to identify—let alone report—potentially covered transactions. U.S. businesses fighting for market share in China could find their efforts to upgrade their factories hobbled. Foreign businesses in the U.S. would also be affected, making the U.S. a less attractive place to invest, especially in the high technology sectors where we want to lead.

For these reasons, legislators now working to resolve differences in the House and Senate bills should consider what provisions should stay and what should go. Lawmakers should support measures that boost government spending on R&D, particularly where it helps small businesses compete in the global marketplace. And they should drop provisions that add bureaucratic red tape and uncertainty for businesses.

But it doesn’t end there. We also need to take a hard look at what our current policies are doing to U..S scientists of Chinese heritage. The China Initiative, a Department of Justice program ostensibly aimed at countering industrial espionage, has led to a string of unfounded accusations against scientists of Chinese heritage, who account for nearly 90% of cases under the initiative. This has had a chilling effect on Chinese American scientists who worry that their next big innovation could put them under suspicion.

For the U.S. to compete effectively, we need to be smart. That means putting our strengths—and our values—first.

This editorial first appeared on South China Morning Post.